Medellín, Colombia — After President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s historic re-election in October last year, the man who was in jail 40 months ago has today completed 100 days of his third presidential term.

“Brazil has a future once more, and this is just the beginning,” he pronounced during a speech marking the milestone.

Prior to the election, Brazil had passed through some of the most turbulent years in its history. The combination of a global pandemic and the controversial, vaccine-denying Jair Bolsonaro plunged the nation into crisis, re-joining the United Nations Hunger Map in 2022.

Receiving just 50.9% of the vote in a run-off election against Bolsonaro, Lula’s task is perhaps the epitome of needing to steady the ship in a heavily polarised society. But how well has he handled his first 100 days at the helm?

Here is a look at some of the key areas Lula has had to deal with so far.

Managing a divided Congress

Lula, a lifelong union man and member of the left-leaning Workers’ Party (PT), stepped into office amid a predominantly conservative Congress, in which he was tasked with obtaining the necessary support to pass new legislation.

Gustavo Uribe, political analyst at CNN Brasil, told Latin America Reports, “Lula doesn’t have a solid foundation of support. With just those who support him in Congress, he can’t achieve anything, so he’s going to have to compromise.”

And compromised he has, handing nine out of 37 ministries to the Social Democratic Party (PSD), the Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB) and the Brazil Union (UB), three centre-right parties who have historically opposed Lula’s PT.

He also supported the re-election of Arthur Lira as the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Brazil’s lower house. Lira is a member of the Progressistas (PP) and was previously in alliance with Bolsonaro, shielding the former president from dozens of impeachment requests.

Any new legislation must be passed through Lira, meaning that Lula’s relationship with him is a pivotal one.

Uribe said that Lula has no choice but to pursue a tactic of “coalition presidentialism, providing positions and funding to members of opposition parties in order to receive their backing.”

However, he stressed that in doing so, Lula “runs the risk of another Mensalão,” the vote-buying scandal which took place during Lula’s first term as president (2003-2006), underlining that he “must remain aware so that history does not repeat itself.”

In June 2005, Brazilian deputy Roberto Jefferson revealed to newspaper Folha de S.Paulo that the PT paid several deputies 30,000 reais per month to vote for the government’s favored legislation. The funds were reportedly sourced from state-owned companies’ advertising budgets.

Just before taking office, Lula narrowly escaped a political pickle as the Supreme Court ruled that a shadowy vote-buying scheme that operated during Bolsonaro’s administration, known as Brazil’s “secret budget,” was unconstitutional.

Lula’s public criticism of the scheme during the election campaign was bold, as he was going after a Congress which may have been complicit in the wrongdoing. Fortunately for the current president, the Supreme Court’s ruling effectively alleviated him of the matter.

Read more: Brazilian Supreme Court declares Bolsonaro’s secret budget unconstitutional

The environment

Environmental protection was a leading talking point in Lula’s presidential campaign.

Former President Bolsonaro received widespread criticism for his disregard of the Amazon Rainforest during his administration. According to government figures, deforestation rose 150% during his final month in office.

Four years ago, Germany and Norway pulled out of the Amazon Fund, losing confidence in Bolsonaro’s ability to govern it after the former president unilaterally closed the fund’s steering committee in August of 2019.

Since Lula’s return to office, both Germany and Norway have resumed their contribution to the Amazon Fund, and United States climate envoy John Kerry signaled in March that the US may also start contributing to the fund.

“We very much like the model that was developed during the former presidency of Lula and we want to continue to work closely on that path,” Espen Barth Eide, Norway’s Minister of Climate and the Environment, told reporters after meeting his Brazilian counterpart Marina Silva.

Dr. Claudia Leonor Lopez Garcés, anthropologist at the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi in Belém, a research institution, told Latin America Reports that the return to funding “represents a shift in government focus from the previous administration, giving priority to action to support the Amazon and its peoples.”

“I think this will materialize as financing to specific projects for the Amazon which can be considered of vital importance for the strengthening and reclaiming of the socio-cultural processes within the Amazon,” she continued.

Uribe agreed with the significance of this development, stating, “It shows that Brazil has returned to being concerned with the environment. This bridges the gap between the EU and South America and could lead the way to further collaboration.”

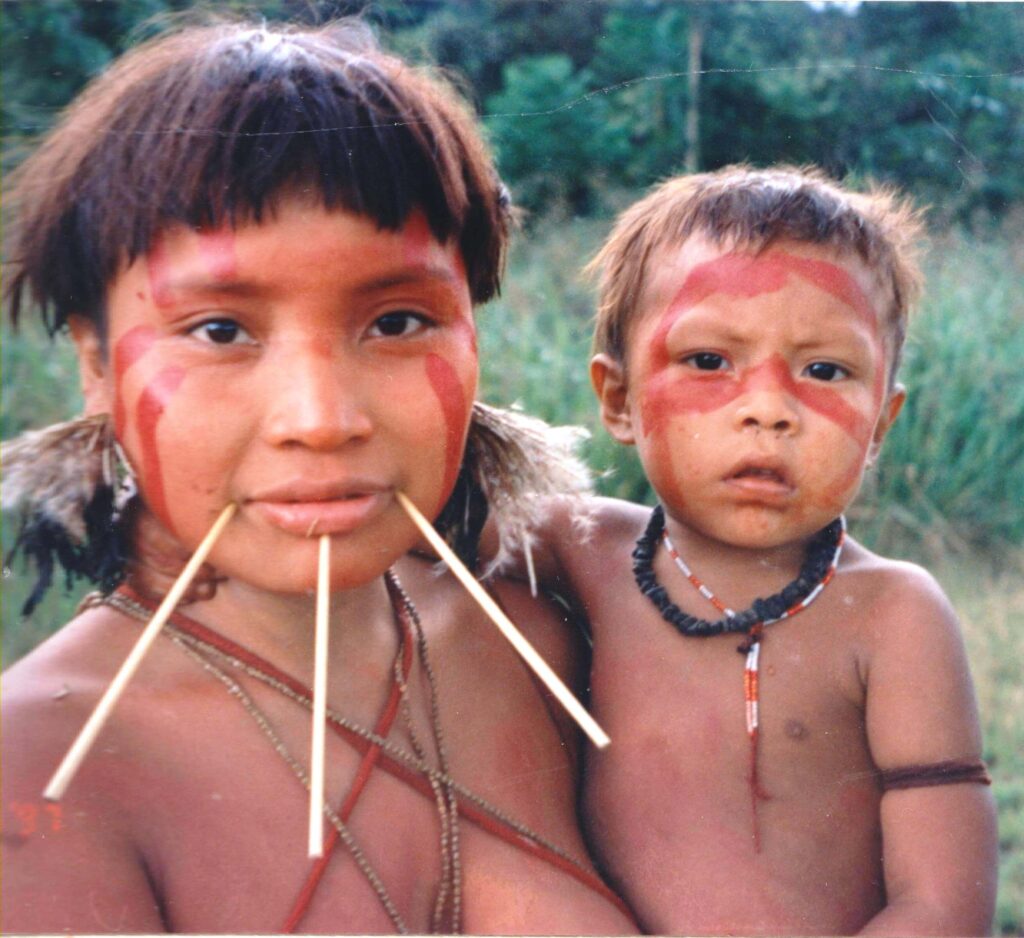

Lopez also applauded Lula’s appointment of two internationally celebrated Amazon defenders as ministers in his new government. “The implementation of the ministry of Indigenous peoples is key, especially with Indigenous leader Sônia Guajajara appointed minister,” she explained.

Guajajara will lead Brazil’s first ever ministry for Indigenous peoples. It was established in reaction to the surge of aggression and encroachment on land provoked by Bolsonaro’s efforts to abolish protections for Indigenous communities and the environment.

“These are already very concrete actions [from Lula’s administration] and are fundamental to be able to make changes to federal laws which will help to protect the Amazon and its inhabitants,” Lopez continued.

In the final week of March, Lula requested Congress to drop Bill 191, which would allow mining on Indigenous lands. Bolsonaro’s administration had tried to push this bill through Congress.

The new president is also stepping up security measures for Indigenous territories. Earlier this year, Lula deployed the army to reclaim Brazil’s largest Indigenous reserve, the Yanomami territory on the northern border with Venezuela, from thousands of illegal gold miners who had occupied the area and triggered a humanitarian crisis.

However, political analyst Uribe stressed that Lula still has work to do:

“So far, the [deforestation] numbers have not been good. In order to be able to truly say that this is a change from the Bolsonaro government, Lula has to show a decrease in deforestation rates. This would be via an increase in police in the Amazon, strengthening the organizations enforcing laws and monitoring, a greater presence of federal police, as well as the destruction of illegal mines.”

According to Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE), February 2023 recorded a 61.8% increase in deforestation alerts in the Amazon.

Lopez pointed out that, “The statistics are delayed, provided long after the damaging actions take place.” She continued, “This recent increase reflects the mismanagement of the previous government, who gave too much freedom to agribusinesses and miners to establish themselves continuously in the Amazon.”

In January, Brazil made an official bid to host COP30 in 2025 in the north-eastern city of Belem. Uribe described Brazil as “frontrunners,” adding “it would elevate the country’s position in the discussion surrounding the environment.”

Public health

With one of the world’s largest universal and free-of-charge public health systems, Brazil has a commendable track record in disease control and vaccinations. For instance, in 1980, the country vaccinated 17.5 million children against polio in a single day, and in under four months in 2010, over 89 million doses of the swine flu vaccine were administered.

Under Bolsonaro’s administration, however, vaccination rates plummeted. In 2021, data on child vaccination reached its lowest point in over 30 years.

The former president was opposed to the use of masks and social distancing measures, likening the coronavirus to rain that would only affect a few individuals.

In August 2021, Pfizer offered Brazil 70 million doses of the vaccine, which would have been delivered starting in December, but the government declined the offer. Following the registration of 1,452 deaths on a single day, Bolsonaro remarked, “It’s no use staying home crying.”

Lula’s task, then, has been to recover the nation’s faith in immunisation programs.

On February 27, he received his fifth Covid-19 vaccine on camera. “The vaccine is a guarantee of life,” he pronounced. “I would like to call on every mother, every grandmother, every father, every teenager, every child […] not to believe the nonsense that is being said about vaccines.”

The event helped launch the Ministry of Health’s National Movement for Vaccination, a campaign aimed at restoring high vaccination rates.

Read more: Brazil pushes to recover vaccine rates lost during Bolsonaro administration

It marked the start of Brazil’s administration of a bivalent COVID-19 vaccine, first offered to 54 million people in vulnerable groups, including people over 60, Indigenous communities, pregnant women and the immunocompromised.

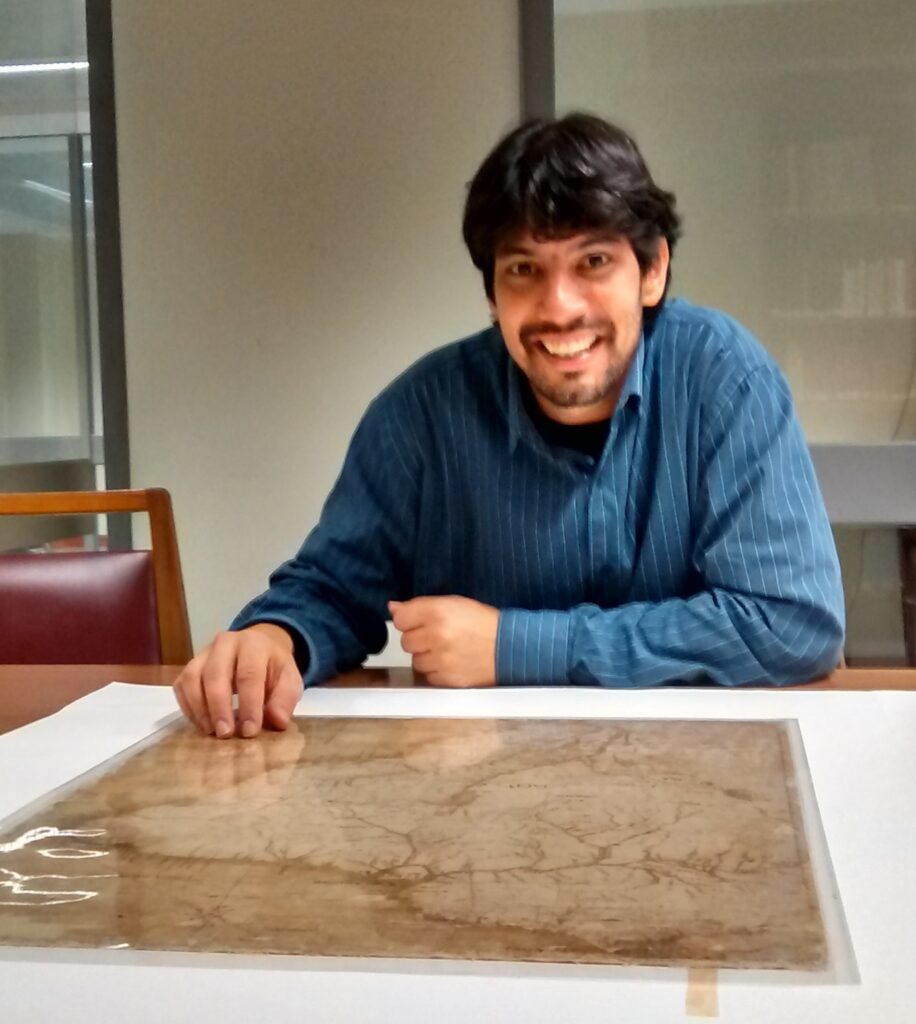

Dr. André Reyes Novaes, human geographer at Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ), told Latin America Reports, “this was a very significant moment.”

Novaes highlighted the role of Nísia Trindade, Brazil’s first female health minister, at the event. She gave a speech commemorating the vaccination program and the return of Zé Gotinha, a cartoon character created nearly 40 years ago to help boost vaccination among children.

Novaes explained, “During our childhood, Zé Gotinha was a part of all the vaccination campaigns. The idea was to have someone who would appeal to kids and stimulate vaccination uptake. […] When the pandemic arrived, people would often ask: where is Zé Gotinha? Because the previous government simply did not establish a pro-vaccination campaign. His return is a very symbolic factor.”

Novaes was also keen to stress the importance of Trindade’s election as health minister, stating “it is perhaps one of Lula’s most significant actions so far. She is technically competent and well respected by Brazilian doctors.”

“She made sure that during the pandemic, vaccines continued to be distributed despite Bolsonaro’s resistance,” he continued.

However, Novaes said that “we still don’t know the real impact this will have on vaccination rates. They are still low in many municipalities and the rate of use of the bivalent COVID vaccine is not yet very high. The urgency to vaccinate against COVID isn’t really there as the death rate is not currently high.”

Poverty and hunger

After being absent from the list for eight years, Brazil returned to the United Nations’ Hunger Map in 2022. The map identifies nations with more than 2.5% of their population facing chronic food shortages. In Brazil, it is estimated that 4.1% of its 215 million inhabitants are experiencing extreme hunger.

One of Lula’s greatest achievements from his first stint as president was the creation of the Bolsa Familia, a social welfare program aimed at reducing social inequalities by linking income transfer to certain conditions, such as school attendance, health, and nutrition.

Novaes praised Lula’s scheme for not being “just a program of financial benefit, but also of social wellbeing,” thanks to the requirements needed to receive the funding.

The Fome Zero program, which was included in the Bolsa Família initiative, aimed to eradicate hunger in the country. It was successful, with Brazil leaving the UN Hunger Map in 2014, earning Lula recognition as a Global Champion in the Battle Against Hunger by the World Food Programme in 2016.

Novaes told us that “the program faced criticism from the right-wing, who suggested that it would remove the incentive for poor families to take initiative and work for their money.”

“When Bolsonaro came to power, he attacked the program, ending it in October 2021,” he added.

That month, the former president claimed that beneficiaries of the scheme “know how to do almost nothing,” suggesting that they become lazy without the need to work to survive.

Shortly before last year’s elections, in May 2022, Bolsonaro launched Auxilio Brasil, a similar social welfare scheme offering 400 reais per month to families in need, with no requirements to obtain the funding.

Commenting on Bolsonaro’s rebranding of the Bolsa Familia, Novaes said, “For me it is very clear that Bolsonaro had electoral intentions. He saw the elections were approaching and introduced the scheme, having removed it the previous year, making it so the poor would receive money independent of what they do.”

Bolsonaro repeatedly claimed that he would increase the funding to 600 reais per month if he were re-elected in October.

“During the election it was interesting that those from the right-wing ceased to question the program, even to the point where they defended it and claimed they wanted to bolster it,” Novaes noted. “Financial benefits became a consensus in Brazilian society, having been so widely criticised during Lula’s previous terms [as president],” he added.

Since coming to power, Lula has reinstated the scheme as the Bolsa Familia, implementing the former president’s proposed increase (to 600 reais per month), with over 20 million families receiving the payment.

Lula restructured the anti-poverty program, which now requires beneficiaries to meet certain requirements, including sending their children to school, getting vaccinated, and undergoing prenatal check-ups.

“This is not a programme of a government or a president, it is a public policy of Brazilian society to combat hunger and extreme poverty,” tweeted the head of state on March 2.

However, Novaes said that “[funding the scheme] is an immense challenge at the moment […] The government is going to have to find fiscal tools to be able to finance the program without compromising other areas and maintaining a sustainable level of spending.”

“We hope that the program can yet again remove Brazil from the UN’s world hunger map, just as it did in 2014,” he added.

The economy

One of the main concerns surrounding Lula’s arrival to power has been how he will deal with Brazil’s unstable economy.

Dr. Otto Nogami, an economist at the Institute of Education and Research (INSPER), told Latin America Reports that some of Lula’s biggest economic tasks include “resuming the process of sustainable growth, […] improving the public debt/GDP ratio […] as well as structural conditions such as education, health, and public security, […] and reinserting the nation into the international economic sphere.”

Lula has come under fire for his strong criticism of the Central Bank for the nation’s high interest rates. Two weeks ago, the rate reached 13.75%, an extraordinarily high figure, especially when considered alongside Brazil’s 2% rate seen at the start of 2021.

“I will keep knocking, I will keep trying to fight so that we can reduce the interest rate, so that the economy can have investment,” Lula said in an interview with Brasil247.

For Nogami, however, “[Lula] is dealing very badly with the interest rate.” The economist explains, “His discourse is merely political. Yet, the interest rate does not depend on politics.”

“I usually say that the interest rate portrays the structural conditions of the economy. If these conditions are bad, we tend to have higher interest rates and, as we invest in structural improvements, these rates tend to be lower,” he added.

Another worry is that Lula’s clash with the Central Bank is throwing an air of instability over the nation’s economic situation, reducing the confidence of foreign markets looking to invest in Brazil.

Nogami explained, “In the face of this institutional political instability, the outlook for company profits is reduced, causing a loss of interest in stock market shares and leading to a fall in share prices.”

“The same happens with foreign capital,” he added. “They leave in search of more stable markets, which may lead to the devaluation of the national currency.”

For Uribe, however, Lula’s strong stance on high interest rates is no longer damaging his credibility.

“Initially it was bad [for Lula]. But there have been movements from the Brazilian financial market and economists from all over the world criticising the rate, because 13.75% is simply too high,” he stated.

Indeed, a Datafolha study from the end of March showed that 80% of Brazilians now agree with Lula’s regular pressuring of the Central Bank.

Uribe believes that Lula’s stance has helped “to put a lot of pressure on.” He added that “it’s possible the Central Bank begins lowering the interest rates from June, thanks to this pressure.”

Uribe added that, in his opinion, Lula’s proposition for a new tax framework “is perhaps his best work so far,” praising his sensible and diplomatic approach.

“People expected Lula to act ideologically, like at the end of his second term, rather than pragmatically,” he explained. “When Lula proposed to end Brazil’s spending limit, the expectation was that he would spend too much.”

“But, he made a good rule. The financial markets liked it, the more conservative sectors of society liked it, the opposition parties liked it. Bolsonaro’s party, for example, wishes to vote in favor of the proposal. And even the left-wing parties that wanted to spend more are finding it a good proposal. So, he managed to deal with it well, calling everyone into the discussion.”

“The fact that he gave Lira the power to nominate the rapporteur of the proposal in the chamber of deputies helps since it places the onus on the opposition party. If it doesn’t work, it’s also Lira’s fault,” he added.

Uribe pointed out that we are yet to see the true effectiveness of Lula’s parliamentary compromise, “because there is yet to be an important vote,” adding that the vote on a new tax framework in May will be a good litmus test.

“We’re building a new chapter in the history of Brazil,” Lula said in his speech commemorating his first 100 days.

Defiant as ever, it seems that Brazil’s president has, so far, avoided disaster. While 100 days is not nearly enough time to pass definitive judgement, Lula’s latest approval rating (41%) tops that of Bolsonaro’s first months in charge (34%).

The remainder of this year will paint a clearer picture as to whether Lula has been able to bridge the gap between two halves of a profoundly divided nation.